Breaking Down Hamstring Strains: Anatomy, Injury, and Recovery

It’s a perfect day outside, the temperature is just right, and your mind is set on achieving today’s goal. Maybe it’s a long run down the West Side Highway, a tempo effort in Central Park, or scoring a goal for your pickup team on the fields at McCarren Park. Everything feels just right. Then, out of nowhere, lightning strikes, and the perfect day is suddenly filled with grey clouds.

You just felt a sharp pull in the back of your thigh that stops you in your tracks. Caught off guard, you pause, trying to process what just happened. That sudden jolt? It’s a hamstring strain. Maybe it’s your first. Maybe it’s not. The questions start rolling in: what happened, why now, and what comes next?

Research shows that hamstring strains are extremely common, especially in athletes who run, sprint, or play sports like soccer and football. The bad news? If you’ve had one before, your risk of re-injury can be up to six times higher. It is estimated that nearly one third of those who have experienced one will have a reoccurrence within a year after returning to sport. The good news? There are ways to reduce that risk and build hamstring strength that holds up under the demands of your sport.

To better understand hamstring strains, let’s take a closer look at hamstring anatomy, what these muscles do, why injuries happen, and how we can approach recovery and prevention.

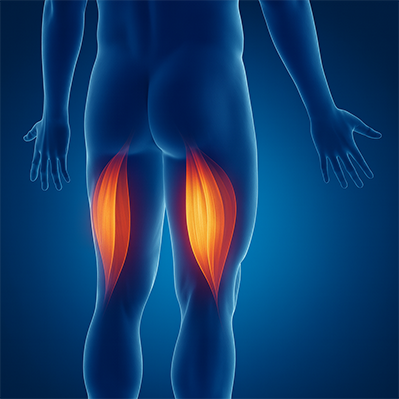

Hamstring Anatomy and Function

The hamstrings are a group of three muscles: the Biceps Femoris, Semitendinosus, and Semimembranosus. They run along the back of the thigh and connect from the pelvis, often referred to as the hip, to just below the knee on the bones of the lower leg. Their job is to assist with hip extension, the backward movement of the leg, and knee flexion, the bending of the knee. They’re active in everyday movements like walking and standing, as well as in more dynamic and explosive actions like sprinting, jumping, and quick changes of direction commonly seen in sports.

To better understand the hamstrings’ function in running, it helps to look more closely at how they work during different phases of movement. Let’s look at those phases and see what the hamstrings are doing.

Terminal swing: is the final part of your leg’s forward motion before the foot strikes the ground. During this phase, the hamstrings become very active. As the leg swings out in front of you, the hamstrings work to slow it down and help control the motion, preventing excessive straightening at the knee.

Heel strike: is the moment your foot first makes contact with the ground. When it happens, there’s a quick spike in force that travels up through the leg. That force pushes the hip into more flexion (bending) and the knee toward full extension (straightening). The hamstrings have to kick in to help control that motion and prevent the leg from moving too far in either direction.

Push-off: happens at the end of the stance phase, just as your foot is leaving the ground. During this moment, the hamstrings assist with driving the leg back and helping the body move forward.

The hamstrings also play an important role in stabilizing the knee. Working alongside the ACL, the hamstrings help prevent the lower leg from sliding too far forward when your heel strikes the ground.

Injury: Why It Happens and What Increases Risks

We’ve walked through how the hamstrings function during the different phases of running, particularly the moments when injuries are most likely to occur. Now we’ll look at why these injuries happen and what puts someone at greater risk.

There are several reasons a hamstring strain might happen, and not all of them are within our control. Some risk factors cannot be changed, like age or history of previous injury. Others are considered modifiable, which means we can do something about them.

Here are some of the most common modifiable risk factors:

Inadequate warm-up

Jumping into high-speed movement without preparing the muscles increases the chance of strain.

Muscle fatigue

As the body tires, muscles lose their ability to absorb and control force, making them more vulnerable.

Dehydration

Without enough fluids, muscle function declines, which can increase the risk of injury.

Limited flexibility in the lower body

Tightness or restriction in the hips, hamstrings, or surrounding muscles can lead to altered movement and added strain.

Poor core or pelvic stability

A weak or unstable core affects alignment and movement control, often shifting more stress onto the hamstrings during high-speed efforts.

Muscle weakness or imbalance

Hamstrings that are undertrained or significantly weaker than surrounding muscles are more likely to struggle under load.

Deconditioning

Time away from training or inconsistent activity levels can lower strength, endurance, and neuromuscular control, making it harder for the body to handle athletic demands.

When we look back at the gait cycle, especially during terminal swing and heel strike, it becomes clearer why these risk factors matter. During these phases, the hamstrings are working eccentrically, which means they are contracting while lengthening. As the leg swings forward, the hamstrings are being stretched but still need to stay engaged to help control movement at the hip and knee. If they are fatigued, weak, or not properly warmed up, their ability to manage that load drops. That is when the risk of overstretching or tearing goes up.

Grades of Hamstring Strain: What They Mean

Not all hamstring strains are the same. Some feel like a mild pull that loosens up after a few days, while others can sideline you for weeks or even months. Clinically, hamstring injuries are grouped into three grades based on how much damage has occurred.

Grade I: Mild Strain

This might feel like tightness, slight discomfort, or a small pull during movement. You can usually walk and maybe even jog, but sprinting or quick changes in direction don’t feel quite right. In this case, only a small number of muscle fibers have been overstretched or slightly torn. There’s no significant loss of strength or flexibility, and recovery tends to happen within one to three weeks with proper care.

Grade II: Moderate Strain

This level of injury is more noticeable. You may feel a sharper pain during activity, followed by swelling, tenderness, or bruising. Walking might be uncomfortable, and running is usually not possible. A Grade II strain often involves a partial tear in the muscle or tendon. There is usually a visible decrease in strength and flexibility. Recovery time typically ranges from four to eight weeks and often includes a structured rehab program.

Grade III: Severe Strain or Complete Tear

This is the most serious type of hamstring injury. You may feel a sudden and intense pain, sometimes described as a “snap” or “pop”, followed by immediate weakness or an inability to continue moving. Putting weight on the leg may be difficult, and there may be noticeable bruising, swelling, or even a visible lump. A Grade III strain usually means a full tear of the muscle or tendon. In some cases, the tendon may even pull away from the bone, known as an avulsion. Recovery often takes several months, and surgery may be needed depending on the extent of the injury.

Understanding the severity of your strain is just the first step. Next, we’ll look at how to approach recovery and how to return to doing what you love with confidence.

Recovery Through Physical Therapy

Recovering from a hamstring strain is not just about waiting for the pain to go away. A structured physical therapy plan is important to healing properly, rebuilding strength, and reducing the risk of reinjury when returning to sport

In the early days, treatment usually focuses on reducing pain, restoring movement in gentle, small increments, and beginning light muscle activation. This stage is crucial because it helps prevent excessive scar tissue from forming, which can interfere with proper muscle fiber regeneration in the injured area and increase the risk of reinjury later on.

As the healing process continues, therapy shifts toward regaining full strength, improving flexibility, and addressing any movement limitations or imbalances that may have contributed to the injury in the first place. Recovery should also include training the entire kinetic chain, which means building control through the core and pelvis. Research has shown that physical therapy programs incorporating lumbopelvic stabilization and movement retraining are more effective at reducing reinjury rates than hamstring focused protocols alone.

One of the most important tools in this phase is eccentric strength training. Eccentric exercises challenge the muscle while it lengthens, which is exactly what the hamstrings are doing during the phases of running where injuries often occur. Among the most effective of these is the Nordic hamstring curl exercise. This movement targets the hamstrings through controlled lengthening, and research supports its ability to build strength and lower the risk of future strains.

As you approach the final stages of therapy, the focus shifts to gradually reintroducing speed and power through functional drills. Over time, your exercises should begin to mirror the demands of your sport such as running, cutting, and acceleration, so your return feels both safe and confident.

Key Takeaways

1. Hamstring strains are common in running and high-speed sports, with a high chance of reinjury if not properly addressed.

2. Most injuries happen when the hamstrings are lengthening under load during phases like terminal swing and heel strike.

3. Risk increases with fatigue, poor warm-up, core instability, tightness, or muscle imbalance.

4. Recovery requires a structured rehab plan that includes core and pelvic training, not just hamstring work.

5. Eccentric exercises like Nordic hamstring curls are proven to build strength and lower the risk of future injury.

Interested in other ways to build strength and improve your resilience? Check out our other blogs for more insights on other types of training. Curious about how physical therapy or a personalized training program can help you? Schedule a free discovery call at (917) 494-4284.

Works Cited

Arner, Justin Wade MD; Rothrauff, Ben MD, PhD; Bradley, James Phillip MD. Hamstring Injuries in Athletes: Anatomy, Pathology, and Treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 33(13):p e703-e714, July 1, 2025. | DOI: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-24-01162

Bramah, C., Mendiguchia, J., Dos’Santos, T. et al. Exploring the Role of Sprint Biomechanics in Hamstring Strain Injuries: A Current Opinion on Existing Concepts and Evidence. Sports Med 54, 783–793 (2024).

Chu SK, Rho ME. Hamstring Injuries in the Athlete: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Return to Play. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2016 May-Jun;15(3):184-90. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000264. PMID: 27172083; PMCID: PMC5003616.

Chumanov ES, Heiderscheit BC, Thelen DG. Hamstring musculotendon dynamics during stance and swing phases of high-speed running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 Mar;43(3):525-32. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181f23fe8. PMID: 20689454; PMCID: PMC3057086.

Lehto MU, Järvinen MJ. Muscle injuries, their healing process and treatment. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1991;80(2):102-8. PMID: 1897874.

Järvinen MJ, Lehto MU. The effects of early mobilisation and immobilisation on the healing process following muscle injuries. Sports Med. 1993 Feb;15(2):78-89. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199315020-00002. PMID: 8446826.

Rodgers CD, Raja A. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hamstring Muscle. [Updated 2023 Apr 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.