Everything you need to know about Strength Training for Runners

Runners love to run, and understandably so. However, many runners neglect one of the most important areas of fitness: strength training. Now you might be wondering why bother with strength training? After all, shouldn’t we just run more if we want to get better at running? Well, the answer might surprise you. Strength training not only can improve running metrics, but also has a plethora of benefits including increased bone density and long-term health benefits. But in this modern world full of online resources and social media, there is a surplus of information on strength training that can be overwhelming. Furthermore, understanding how to implement strength training into your already busy work and running schedule can further complicate logistics. But fear no more, as this article intends to cover all of the basics on why and how we can program strength to supplement our running!

What is strength training:

First, let’s define strength training. Webster defines strength as “the quality or state of being physically strong1” Well, on the surface this seems obvious and doesn’t help. To help us further understand strength, we can turn to physics, which defines strength as “the application of force.” While there are numerous sub-categories of strength, when it comes to strength training that is exactly what we are doing: training to apply more force. If we are trying to pick up a 50-pound box, we must be able to produce more than 50 pounds of force to pick up that object. The more force we produce, the stronger we are. Strength is purely looking at force and the speed at which you produce force does not matter. Another misconception is the concept of absorbing force. We don’t actually absorb force; we simply produce it. So if we want to improve our strength, intuition tells us that we should be producing relatively high forces. Does this mean that we have to lift 300 pounds to get stronger? Absolutely not. Strength is relative to the individual. A bodyweight squat might be very hard for someone and can elicit a strength adaptation. On the other hand, if you are able to squat 300 pounds for 10 repetitions, you can do all the bodyweight squats your heart desires, but you are not getting stronger.

Takeaway: strength is force produced and is relative to the individual, it is not velocity (speed) dependent.

Runners love to run, and understandably so. However, many runners neglect one of the most important areas of fitness: strength training. Now you might be wondering why bother with strength training? After all, shouldn’t we just run more if we want to get better at running? Well, the answer might surprise you. Strength training not only can improve running metrics, but also has a plethora of benefits including increased bone density and long-term health benefits. But in this modern world full of online resources and social media, there is a surplus of information on strength training that can be overwhelming. Furthermore, understanding how to implement strength training into your already busy work and running schedule can further complicate logistics. But fear no more, as this article intends to cover all of the basics on why and how we can program strength to supplement our running!

What is strength training:

First, let’s define strength training. Webster defines strength as “the quality or state of being physically strong1” Well, on the surface this seems obvious and doesn’t help. To help us further understand strength, we can turn to physics, which defines strength as “the application of force.” While there are numerous sub-categories of strength, when it comes to strength training that is exactly what we are doing: training to apply more force. If we are trying to pick up a 50-pound box, we must be able to produce more than 50 pounds of force to pick up that object. The more force we produce, the stronger we are. Strength is purely looking at force and the speed at which you produce force does not matter. Another misconception is the concept of absorbing force. We don’t actually absorb force; we simply produce it. So if we want to improve our strength, intuition tells us that we should be producing relatively high forces. Does this mean that we have to lift 300 pounds to get stronger? Absolutely not. Strength is relative to the individual. A bodyweight squat might be very hard for someone and can elicit a strength adaptation. On the other hand, if you are able to squat 300 pounds for 10 repetitions, you can do all the bodyweight squats your heart desires, but you are not getting stronger.

Takeaway: strength is force produced and is relative to the individual, it is not velocity (speed) dependent.

Benefits of strength training:

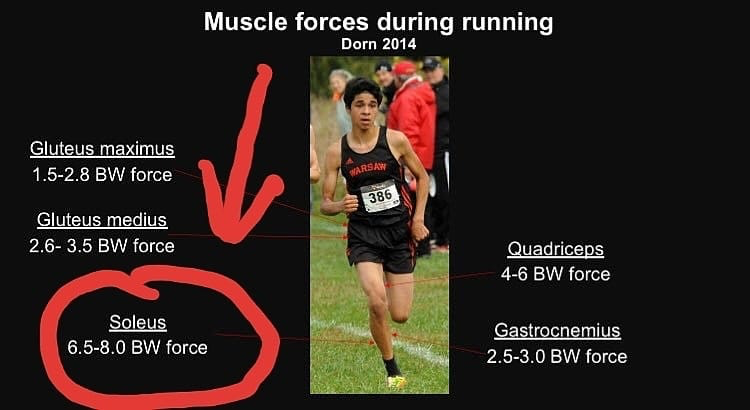

So now that we understand what strength is, we can now talk about why we should be strength training. You might be asking yourself: do I really need to lift heavy weights and produce more “force” when running involves no weights? Well, in fact you do. When we look at the physical demand of running, there is significantly more force being produced than you might think. While running, we experience forces between 2.0-2.9 times our bodyweight2! Furthermore, certain muscle groups can experience forces over 7x our bodyweight as depicted in the picture below. Strength training has been linked to improved running economy for middle- and long-distance runners3. The research even supports strength training being superior to plyometric training4. An often-overlooked benefit of strength training is bone health. Bone-related stress injuries in running are common, and strength training has widely been accepted by the literature to maintain and improve bone mineral density5. While we can’t say strength training will prevent running related bone Injuries, we can certainly say it creates stronger bones that can withstand high forces.

Programming strength training:

We established what strength and strength training are and why it’s important. But none of that matters if we don’t know how and when to program it. As mentioned, strength is extremely relative and context-dependent. There are many variables to consider, the main ones being intensity (weight/load/perceived exertion), volume, frequency, and repetition/set schemes. Let’s start with reps. Strength adaptations typically occur between 1-6 repetitions for 2-6 sets. Keep in mind this is not absolute, but most strength programs will and should be within this range. The most important consideration is intensity. It is typically recommended to work at a percentage of your 1 repetition maximum (1RM) at 80-100%. However, you can certainly still get strength adaptations working at a lower intensity, however it is optimized at heavier loads. Below is a chart to help estimate 1RM. We recommend trying a 5 or 10 rep max as this can be safer, especially for inexperienced lifters or those who do not have a spotter. The last variable is frequency. While there are countless programs with varied rep, set and intensity schemes, we recommend a minimum of 2x/week to ensure recovery and adaptation to imposed stimulus.

Exercise Considerations for runners:

You might be saying “I am running 5x/week and training for a marathon, how and where can I fit that into my training?” Well, we have got you covered. For runners training for a specific event (5k, 10k, marathon, etc), runs should be prioritized and done prior to the strength training for longer runs. For short to medium runs, we suggest doing your strength work prior. You want to consider whether the strength work will impact the run. The longer the run, the higher likelihood it will impact performance. The same goes for strength training. Strength sessions should be spaced out with at least 1-2 days between them. Performing strength sessions between runs or on lower volume run days can be helpful. Strength training sessions for runners should focus on big muscle groups that are used for running, such as quadriceps, hamstrings, glute, groin and calves. Typically between races, or during the “offseason” is when you should and can focus on higher intensity strength work. For sports, the goal is to maintain strength in season, and develop strength during the offseason, therefore finding a time during the year where you are between races or reducing volume can be a great opportunity to temporarily shift the focus to high intensity strength training.

Exercise recommendations:

So I know what you’re thinking: “get to the point, what exercises should I do.” And I don’t blame you. The reality is, we can get stronger with any movement or exercise, and there is no perfect one. But as we discussed, runners need to strengthen their legs. A good starting point is picking 1 exercise that focuses on hip dominant strength (deadlift variations, bridges, hip thrusts, etc), and 1 exercise that focuses on knee dominant strength (squat, split squat, lunges, etc) and split them between day 1 and day 2. You can then add in the other muscle groups to create a balanced program. Running is a single leg activity, so it can certainly be beneficial to incorporate single leg strength training. However, double leg exercises are equally beneficial as the goal is to improve overall strength through progressive loading. If you want more information on programming for strength training for runners, we offer training that includes a customized program to help reach your goals: https://usindiatax.in/perfectstridept/personal-training-for-sports-performance-in-new-york-city/

In conclusion, we should aim for strength training 2-3x/week, working through higher intensities with low reps and training bigger muscle groups such as the quads, glutes, hamstrings and calves. Working multi-joint movements such as deadlifts, squats, lunges are recommended. Remember, everyone has a different starting point, and for many inexperienced lifters simple bodyweight exercises can be enough to elicit a strength response initially. So what are you waiting for, those weights aren’t going to lift themselves.

Works Cited

1: Definition of STRENGTH. Merriam-webster.com. Published 2019. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/strength

2: Nilsson, J., & Thorstensson, A. (1989). Ground reaction forces at different speeds of human walking and running. Acta physiologica Scandinavica, 136(2), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.1989.tb08655.x

3: Llanos-Lagos, C., Ramirez-Campillo, R., Moran, J., & Sáez de Villarreal, E. (2024). Effect of Strength Training Programs in Middle- and Long-Distance Runners’ Economy at Different Running Speeds: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 54(4), 895–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01978-y

4: Eihara, Y., Takao, K., Sugiyama, T., Maeo, S., Terada, M., Kanehisa, H., & Isaka, T. (2022). Heavy Resistance Training Versus Plyometric Training for Improving Running Economy and Running Time Trial Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports medicine – open, 8(1), 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-022-00511-1

5: O’Bryan, S. J., Giuliano, C., Woessner, M. N., Vogrin, S., Smith, C., Duque, G., & Levinger, I. (2022). Progressive Resistance Training for Concomitant Increases in Muscle Strength and Bone Mineral Density in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 52(8), 1939–1960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01675-2